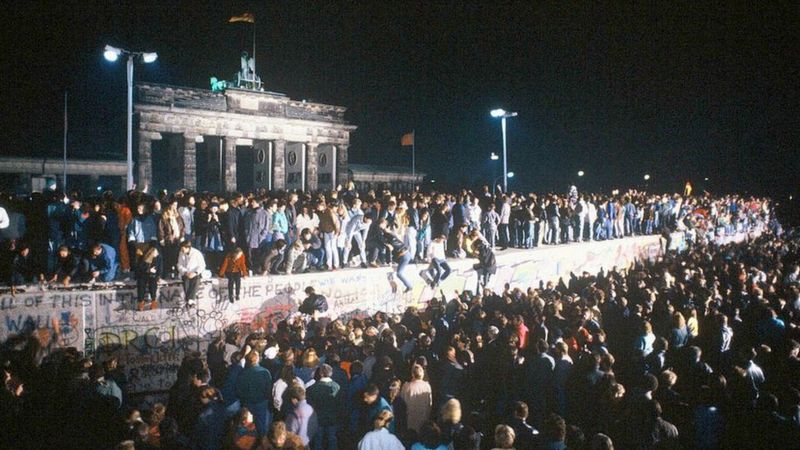

Berlin Wall at the Brandenberg Gate, November 9, 1989

The 40th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall has turned out to be a sombre occasion. Certainly, the euphoria that Europe witnessed on November 9, 1989 has evaporated. The impetus for deeper European integration, manifest in the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, which established a framework for a common currency and a common defence and security policy has petered out; and, the hopes raised by the 2007 Lisbon Treaty that created the EU’s current structure, are no longer there.

To be sure, EU membership jumped from fifteen to twenty-seven during the period from 2004 to 2007, with the addition of central European countries including the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia, as well as the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. But the underlying expectations of a united Europe have been belied and the EU enlargement itself has been mothballed even as the continent struggles with economic crises, migration pressures, and rising nationalism.

German reunification has brought to the fore once again the ‘German question’ albeit in a different form — Germany’s role in Europe. Without doubt, Germany has emerged as the dominant power in Europe. Following the unification, extensive labor market reforms and a manufacturing boom made Germany the undisputed economic powerhouse of the continent.

In turn, Germany’s leadership role — such as its prescription of strict austerity policies and structural reforms as a condition for EU bailouts — and its migration policy by allowing entry to more than one million refugees from Africa and the Middle East has raised raging controversy.

Meanwhile, the bedrock of the European project built on the postwar alliance between Germany and France over economic, defence, and foreign policy is not only transforming with the the balance of power steadily shifting in Germany’s favour, but the two countries have been advancing competing visions for the EU — although German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron have sought to bridge these differences and pledged a common eurozone budget, an independent EU army and more economic integration.

Ironically, the fall of the Berlin Wall has posed an existential dilemma for the western alliance system. The NATO, which was conceived in 1949 as an alliance to protect Europe from Soviet threat, has outlived its original mission and is in search of a raison d’être. Washington addressed this ‘identity crisis’ by pushing for NATO’s eastward expansion toward Russia’s western borders, disregarding Moscow’s virulent objections.

In 1999, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland became members of the alliance; seven more Central and Eastern European countries joined the alliance in 2004. Eight former Warsaw Pact members joined the European Union in 2004, with Romania and Bulgaria following in 2007. Today, NATO counts 29 members (30 once North Macedonia joins) — all dressed up and nowhere to go.

The NATO being the principal vehicle for the US’ transatlantic leadership, Washington cannot do without it and has taken the easy route of recasting Russia in an enemy image — although many European countries remain sceptical. The issue has divided EU leaders, including France and Italy, are openly seeking closer diplomatic ties with Russia.

On the other hand, after a series of snubs to Russia — NATO expansion, dismemberment of the former Yugoslavia and the NATO bombing of Serbia (without a UN mandate), invasion of Iraq, etc. — Moscow’s patience ran out when the US and its European allies pushed for ‘regime change’ in Ukraine in 2015.

The alienation of Russia prompted it to seek the pivot to China and has engendered the Russia-China entente, as both great powers began feeling increased pressures by the US. Beijing and Moscow recognise the potential synergies of joining forces. Apart from a dynamic trade and economic relationship of mutual benefit, China and Russia have not only expanded military cooperation but are also undertaking more extensive technological cooperation, including in fifth-generation telecommunications, artificial intelligence, biotechnology and the digital economy. This complex relationship, categorised as a ‘comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination for a new era’, is steadily acquiring a global character.

Looking back, the triumphalism over the fall of the Berlin Wall glossed over the compelling realities of the world order in transition. The steady decline and loss of influence of the US as world leader, capitalism in crisis in the western industrial world, the rise of China, the emergent global challenges that are not possible for any ‘superpower’ to address on its own steam and the ensuing multipolarity in the international system — all these have tempered the triumphalism forty years ago that ‘history had ended’.

In Europe itself, the vision of unity, regional integration, and cross-border cooperation that the dismantling of the Berlin Wall inspired has come under increasing pressure from newly rising populist and Eurosceptic political forces. Low growth and the migration crisis have caused an overall depletion of morale in the European mind. Brexit is the most dramatic manifestation of it. Populist parties have been on the ascendancy across Europe.

Clearly, added to this, the drift in the transatlantic relationship following President Trump’s confrontational approach raises unprecedented doubts in the European mind. In a recent interview with the Economist magazine — against the backdrop of the 40th anniversary of the fall of Berlin Wall — French President Emmanuel Macron said, “Europe is gradually losing track of its history; secondly, a change in American strategy is taking place; thirdly, the rebalancing of the world goes hand in hand with the rise—over the last 15 years—of China as a power, which creates the risk of bipolarisation and clearly marginalises Europe… Finally, added to all this we have an internal European crisis: an economic, social, moral and political crisis that began ten years ago.”