The optics of the Russian oil leviathan Rosneft’s decision to sell its subsidiary Rosneft Trading SA and sell all its assets in Venezuela after the US Treasury sanctioned its trading arm two weeks ago as part of Washington’s regime change project to oust president Nicolás Maduro, may not look good to the uninformed outside observer.

It may appear, prima facie, that Russia is ditching Maduro and succumbing to US president Donald Trump’s latest act of weaponisation of sanctions against the Venezuelan government. At least, that was how the BBC Radio’s morning bulletin today projected the development.

But as one digs deeper, it emerges, on the contrary, that the Kremlin is having the last laugh. What Russia is doing is, funnily enough, borrowing from the US diplomatic toolbox — the equivalent of what the US does constantly in its war on terrorism, that is, whenever a terrorist group that Washington sponsors gets exposed on the battlefield, it gets promptly rebranded and reappears as a new avatar, and life moves on.

So, what is happening needs to be understood as follows: Rosneft is disengaging from its trading arm Rosneft Trading SA, the Geneva-based trading subsidiary, in a deliberate ploy to create a firewall against potential US sanctions in future.

This is important for preserving Rosneft’s global operations — Rosneft accounts for about 6 per cent of global oil production — which might otherwise be risking the US sanctions in the downstream.

Rosneft is acting with prudence since, although Rosneft is majority-owned by the Kremlin, it is listed in London, and counts BP and the Qatari sovereign wealth fund as large minority shareholders.

A Rosneft spokesman has ben quoted as saying, “As a public international company, we have made a decision in the interests of our shareholders in the context of the situation that has objectively developed. Now we have the right to expect from American regulators to fulfil their publicly given promises.” The last reference is to statements from the US that sanctions against its trading arm would be removed if Rosneft wound down its Venezuelan business.

Interestingly, an unnamed company owned entirely by the Kremlin will be buying the Rosneft subsidiary and its oil services and trading operations in Venezuela. The deal between Rosneft (headed by Igor Sechin) and the Kremlin (headed by Vladimir Putin) boils down to the latter now directly taking over assets in Venezuela amounting to more than 80m tonnes in oil reserves and oil production of 66,500 barrels a day via five joint ventures with PDVSA, Venezuela’s state oil company.

A Rosneft subsidiary will receive 9.6 per cent of the company’s stock from the Kremlin in exchange for the assets. That leaves with Trump an only remaining option of sanctioning the Kremlin itself if he wants to punish Maduro.

Moscow honed this innovative technique to outwit Trump’s sanctions earlier also in Venezuela when it rebranded a joint-Russian/Venezuelan bank facing US sanctions with the Russian joint-venture partners — VTB and Gazprombank —transferring their shares to the Russian government.

Clearly, the deal between Rosneft and the Kremlin (read between Sechin and Putin — who are of course longstanding associates in Russian politics through thick and thin — gives an unambiguous signal that Moscow is in Venezuela for the long haul, no matter what it takes.

The geopolitical implications are hugely consequential for the future of the Maduro government, enhancing Russia’s overall standing in the western hemisphere and highlighting the limits to US hegemony in its own backyard. (Isn’t it Ukraine in reverse order?) The Latin American countries (and China) will be closely watching, too.

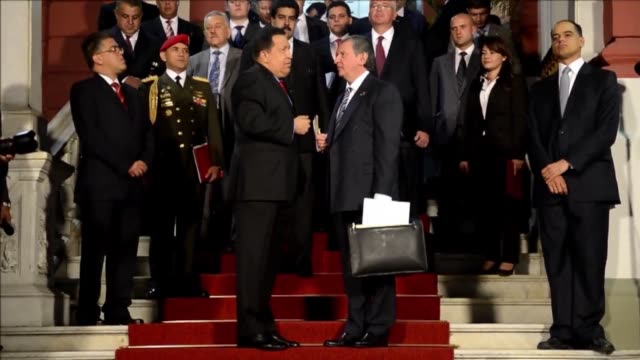

Sechin, a former KGB officer himself, has been a key figure in the Kremlin hierarchy who choreographed and founded Moscow’s close relationship with Caracas. He had an exceptionally warm personal friendship with late Hugo Chavez, the self-styled leader of the ‘Bolivarian Revolution’ in Venezuela. (A 2012 Guardian thumb sketch zeroed in on Sechin as “the head of the Kremlin’s siloviki clan, made up of nationalist hardliners with a security or military background.”)

At any rate, between 2014 and 2018, Rosneft had advanced a loan of $6.5 billion in loans to Chavez to help Venezuela tide over the economic difficulties due to the US’ hostile policies. Venezuela has since mostly paid back the Russian loan in oil deliveries.

Rosneft was marketing between half and two-thirds of Venezuela’s oil and Rosneft Trading SA was Venezuela’s sole supplier of gasoline. The business now will be handled by the unnamed Kremlin company. Evidently, this is a strategic move which signals Russia’s determination to retain its commanding presence in Venezuela’s oil sector.

This has implications for the world oil market, since Venezuela’s proven oil reserves — 300 billion barrels as of 2016 — accounts for over 18 percent of proven oil reserves all over the world and ranks the country as No 1 in the world.

At a time when the OPEC is mutating and the OPEC+ is caught up in the maelstrom of the sharp fall in oil prices due to coronavirus, the future of world oil market has become highly volatile and uncertain. It is already having a deleterious impact on the US shale industry which cannot survive unless oil sells at $45-50 per barrel. But oil prices are certain to go up in the coming years and Venezuela is destined to be a big presence in the world oil market in the long term.

Suffice to say, the Kremlin is playing the long game, while strengthening in the process in immediate terms the Maduro government’s capacity to withstand the US pressure and to retain its strategic autonomy.