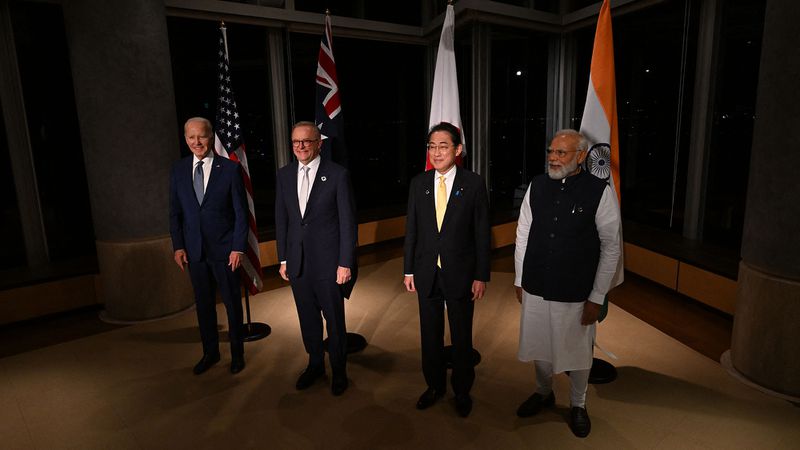

US President Joe Biden, Australian PM Anthony Albanese, Japanese PM Fumio Kishida and Indian PM Narendra Modi held a QUAD meeting in Hiroshima, Japan, 20 May 2023

US President Joe Biden, Australian PM Anthony Albanese, Japanese PM Fumio Kishida and Indian PM Narendra Modi held a QUAD meeting in Hiroshima, Japan, 20 May 2023

This week augurs an acceleration of strategic realignments among the big powers amidst growing signs of a new cold war globally with particular focus on the United States’ containment strategy against China playing out in the Indo-Pacific region. Two back-to-back events on Friday can be seen as major events in this direction.

First, the US President Joe Biden is hosting a trilateral summit at Camp David on Friday with Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol, which is expected to result in the signing of a defence, security and technology cooperation agreement between the three allies relating to the Indo-Pacific.

Second, the annual Malabar exercises participated by the navvies of the US, India, Japan and Australia begins on Friday, hosted by Canberra for the first time, surrounded by much hype that a QUAD collective maritime defence alliance is emerging in the Indo-Pacific.

The trilateral agreement to be signed tomorrow at the Camp David summit reportedly includes ballistic missile defence systems and the development of other high-end defence technologies. Since the election of Yoon last year as the president, South Korea-Japan relations have markedly improved, which helps advance their 3-way cooperation with Washington. Evidently, the Biden administration hopes to take advantage of the recovery of Tokyo-Seoul relations to institutionalise some of the dialogue progress that the three countries have achieved.

The 3-way relationship still remains fragile as Yoon’s efforts are not widely popular within South Korea, and Tokyo, unsurprisingly, remains cautious that the process is far from irreversible. Nonetheless, at the talks at Camp David, Biden, Yoon and Kishida may acknowledge the imperative of collective security for the three countries and agree that a threat to one of them would be considered a threat to all.

Conceivably, the Camp David talks signify an effort by the US to form a new military bloc in Asia and an attempt to encourage Japan and South Korea to join the mini military bloc known as AUKUS [Australia-UK-US]. Washington’s intensification of military-technical and scientific-technological cooperation with Seoul and Tokyo makes it easier for them to interact with AUKUS projects.

As regards the Malabar exercise, its main thrust appears to be to build up QUAD’s operational capability within a collective maritime security strategy in five high-priority areas, including anti-submarine warfare and maritime domain awareness.

Simply put, like AUKUS, QUAD is also transforming, as American ingenuity is creating an alliance-style defence structure on a platform of non-military grouping by strengthening various modes of military cooperation with the intention to make it serve Washington’s interests. Intrinsic to this is the flattering attention President Joe Biden has been paying to India lately — and to Prime Minister Narendra Modi personally.

India’s newfound activism

Interestingly, the US and Australia perceive that the Indian leadership for the first time is showing an ‘‘activism [that] defies conventional skepticism that New Delhi’s preference for nonalignment and its geo-strategic priorities militate against deeper military cooperation with its Quad partners,’’ as an Australian establishment think tanker Tom Corben wrote recently in Nikkei Asia.

That is to say, to quote Corben, Malabar exercises have ‘‘evolved to focus on increasingly sophisticated forms of high-end naval cooperation, particularly maritime domain awareness and anti-submarine warfare… [and] there is a political and strategic window of opportunity for the four countries to make good on this potential.’’ Corben is optimistic that ‘‘bilateral efforts are continuing to open the aperture for tangible Quad maritime defence cooperation.’’

Corben does some kite flying such as India integrating into US-Australia ‘‘force posture initiatives.’’ Earlier in June, he had co-authored a study with two American colleagues at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace titled Bolstering the QUAD: The case for a collective approach to maritime security, which lamented that the QUAD is not ‘‘not living up to its potential as a contributor to regional security and defence in the maritime domain. This is a problem for Indo-Pacific security.’’

In an oblique reference to the Modi government and the rising curve of India-China alienation, the US-Australian study, however, drew comfort that whereas political sensitivities and geo-strategic concerns hitherto prevented QUAD countries from embracing a collective security agenda, ‘‘these constraints are beginning to lessen … as its members come to recognise China as a common military challenge that requires a degree of collective action and security coordination to address.’’

The study recommended that ‘‘QUAD should capitalise on this diplomatic opportunity and geo-strategic imperative to pursue a collective maritime security strategy across five high-priority areas: maritime domain awareness; anti-submarine warfare; maritime logistics; defence industrial and technological cooperation; and maritime capacity building.’’

Importantly, the proposed activities of QUAD would:

- work towards an interface protocol to govern information-sharing between all Quad partners, with particular attention paid to a commonality of hardware and software or, at the least, interoperability of different tools;

- selectively integrate Quad countries’ coastal facilities, island territories and regional access locations to conduct more persistent and coordinated MDA [Maritime Domain Awareness] operations; and jointly assess the requirements of hosting and replenishing one another’s MDA assets like maritime patrol aircraft;

- build collective anti-submarine warfare capability by developing higher levels of interoperability to include tracking and “handing off” overwatch responsibility for Chinese submarines transiting geographic areas of responsibility;

- develop the collective capacity to seamlessly refuel, resupply and repair maritime assets from any member on short notice, and formally commit to this agenda at the political and operational levels;

- establish a QUAD Logistics Coordination Cell within the US Navy’s Commander, Logistics Group Western Pacific that incorporates all four partners and performs logistics planning for the Indian and Pacific Oceans, using combined maintenance and resupply capabilities on a regular basis; and,

- support a framework and requirement for placing QUAD liaisons on one another’s logistics vessels.

Truly radical ‘Machiavellianism’

Evidently, contrary to the Modi government’s theatrical public diplomacy upholding India’s strategic autonomy, an entirely different perception has been generated at the political and diplomatic level with the QUAD partners that ‘‘Barkis is willing’’. This is no small achievement for India’s foreign policy establishment. Max Weber’s famous description of Kautilya’s Arthasastra, one of the greatest political books of ancient India, as ‘‘truly radical Machiavellianism’’ comes to mind.

The paradox is, against such a complex backdrop of opacity or downright doublespeak — depending on how one views it — a contrarian wind may have begun blowing in the weekend presaging some forward movement at the 19th round of India- China Corps Commander Level Meeting held at Chushul-Moldo border meeting point on the Indian side on 13-14 August 2023.

As of now, the evidence is deemed too conjectural but the joint statement exudes a tone of optimism. The two sides considered it necessary to extend the discussion overnight, which has been estimated as ‘‘positive, constructive and in-depth.’’

The protagonists ‘‘exchanged views in an open and forward looking manner’’ and also ‘‘agreed to resolve the remaining issues in an expeditious manner and maintain the momentum of dialogue and negotiations through military and diplomatic channels.’’

It is reasonable to assess that neither India nor China wants a war and that both will maintain a more constant contact with each other as they search for ways to find a solution from which they can both emerge as winners. The core of the guidance provided by the leadership is that the two countries regard each other as a partner, not adversary.

Now, this unstable equilibrium reached at Chushul-Moldo border meeting point will not last if the Malabar exercises turn into a geopolitical tool for Washington to transform QUAD. China had hitherto blithely assumed that QUAD is a mere. papa tiger.

Evidently, the US is stuck in the old Cold War groove despite the drastic changes in international relations that have taken place since the collapse of the Soviet Union, especially those that required the development of new approaches to maintaining strategic stability and building a new architecture of international security.

But the US’ bloc thinking is the opposite of the development of stable, equal, constructive, mutually beneficial relations based on consideration of each other’s interests and aimed at ensuring equal and indivisible security for all. Therefore, its preservation as the main intellectual tool for shaping foreign policy only underscores that the US is not ready, unable or does not intend to build such relations with leading global players such as Russia and China. Implicit in it is a stark message for India, too, that the time has come for it to stand up and be counted as ally.

There is no doubt that the US envisages a pronounced military-strategic dimension to AUKUS and QUAD, which means a high probability of transformation of these interstate associations as cogs in the wheel of a full-fledged military-political bloc sooner rather than later. Its ideological basis is a perceived common interest of its participants to counter the rise of China [which nowadays Delhi euphemistically calls ‘‘multipolar Asia’’].

Suffice to say, as in the case with the NATO on the European theatre, the function of confrontation is planted in the AUKUS and in QUAD, which will inexorably increase the military potential of Australia and the US in the Asia-Pacific region, causing a serious change in the balance of forces and generating a spike in regional and global tensions.

India is at risk of being caught in the eye of the storm, as it were, although its issues with China are neither one of geopolitical rivalry nor of being a gatekeeper for Western hegemony.