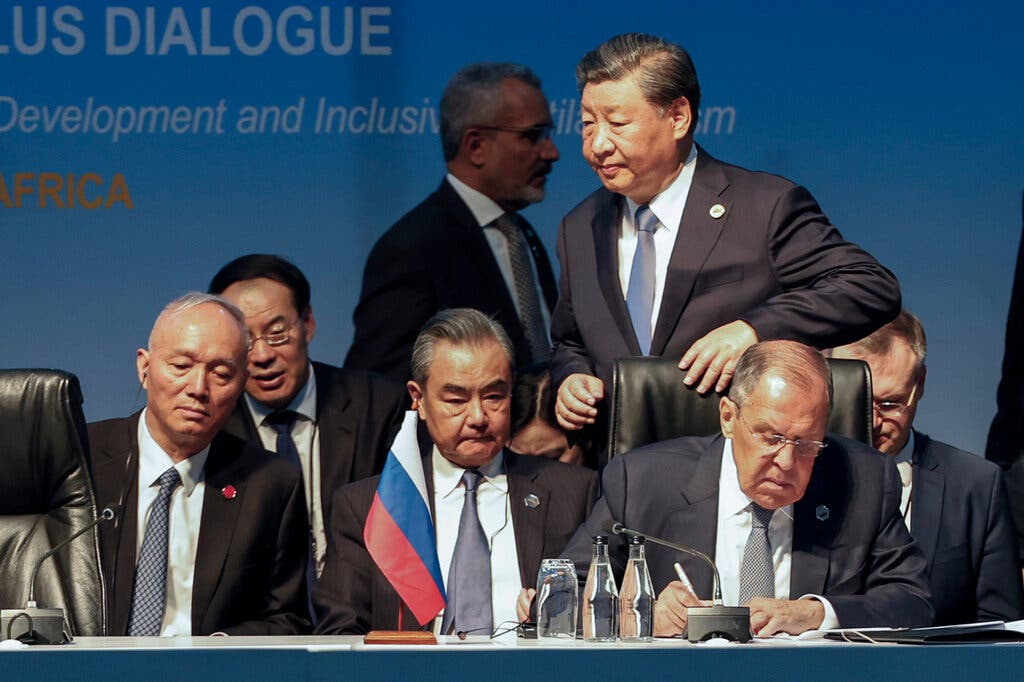

Chinese President Xi Jinping (standing) with foreign minister Wang Yi (C) and Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov (R) at the recent BRICS summit in Johannesburg, South Africa

Chinese President Xi Jinping (standing) with foreign minister Wang Yi (C) and Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov (R) at the recent BRICS summit in Johannesburg, South Africa

The Modi government is not perplexed by the absence of Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping in the G20 Summit on September 9-10. Its intuitive cognition helps to be stoical. This is, arguably, a Shakespearean predicament — “I am in blood / Stepped in so far, that, should I wade no more, / Returning were as tedious as go o’er.”

India’s high-calibre diplomats would have divined some time ago already that an event conceived in the world of yesterday, before the new cold war came roaring in, wouldn’t have the same scale and significance today.

Yet, Delhi must feel disappointed, as the compulsions of Putin or Xi Jinping have nothing to do with their countries’ relations with India. The government has given a bureaucratic spin that “The level of attendance at global summits varies from year to year. In today’s world with so many demands on the leaders’ time, it is not always possible for every leader to attend every summit.”

That said, Delhi administration is sprucing up the city, removing the slums from public view, adding new alluring hoardings to catch the eye of the foreign dignitaries, and even lining flower pots along the roads their motorcades pass.

One doesn’t have to be a rocket scientist to figure out that the common thread in the decisions taken in Moscow and Beijing is that their leaderships are not in the least interested in any interaction with the US President Joe Biden who will be camping in Delhi for four days with all the time at his disposal for some structured meetings, at the very least, some “pull asides” and the like at a minimum that could be caught on camera.

Biden’s considerations are political: anything that helps to distract attention from the gathering storm in US politics which is threatening to culminate in his impeachment that might in turn blight his candidacy in the 2024 election.

Of course, this not Biden’s Lyndon Johnson moment. Johnson made the tumultuous decision in March 1968 to retire from politics as a strong step toward healing the nation’s fissures, while agonising deeply that “There is division in the American house now.”

But Biden is anything but a visionary. He was setting up a bear trap for Putin to reinforce his false narrative that if only the latter dismounted from his high horse, the Ukraine war would end overnight, whereas on its part, the Kremlin is well aware that the White House continues to be the strongest proponent of the thesis that a prolonged war would weaken Russia. Indeed, Biden has gone to extraordinary extents that none of this predecessors ever dared to reach — aiding and abetting Ukrainian terrorist attacks deep inside Russia.

In a way, Xi Jinping also faces a trap, as Biden administration is going to great extent to project itself as conciliatory toward China, as the beeline of US officials heading for Beijing recently would testify — Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken in June; Treasury Secretary and Climate Envoy John Kerry in July; and Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo in August.

The New York Times on Tuesday carried a report titled U.S. Officials Are Streaming to China. Will Beijing Return the Favor? It chastised Beijing:

“China has much to gain from dispatching officials to the United States. It would signal to the world it was making an effort to ease tensions with Washington, particularly at a time when China needs to bolster confidence in its shaky economy. A visit could also help lay the groundwork for a potential, highly anticipated meeting between President Biden and China’s top leader, Xi Jinping, at a forum in San Francisco in November.

“Beijing, however, has been noncommittal.”

The point is, all this while, Washington has also been incessantly taunting and provoking Beijing with belligerence and through calculated means to weaken China’s economy and incite Taiwan and the ASEAN countries to line up as the US’ Indo-Pacific allies, apart from vilifying China.

Both Putin and Xi Jinping have learnt the hard way that Biden is a past-master in doublespeak, saying one thing behind closed doors and acting entirely to the contrary, often being rude and offensive at a personal level in unprecedented display of boorish public diplomacy.

Of course, the symbolism of US-Russian “reconciliation” on Indian soil, howsoever contrived, can only work to Washington’s advantage to pull Modi away from India’s hugely consequential strategic partnership with Russia at a juncture when the West’s entreaties over Ukraine failed to get resonance in the Global South.

As it is, India’s misconceived participation in the recent “peace talks” in Jeddah (which was actually the brainwave of the White House NSA Jake Sullivan) created misperceptions that Modi government “will be part of the implementation of the 10-point peace formula proposed by Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and the details are being discussed.”

Both Moscow and Beijing will be extremely wary of the Biden administration’s booby traps aimed at creating misunderstanding in their mutual relationships and create misperceptions about the stability of the Russian-Chinese strategic relationship at a critical juncture when Putin is preparing to visit Beijing.

Putin’s possible visit to China in October can be considered as a response to Xi Jinping’s March visit to Moscow, but it has a substantial content as evident from Beijing’s invitation to him to be the main speaker at the third Belt and Road Forum marking the 10th anniversary of the appearance of BRI in Chinese foreign policies.

Although in 2015 Putin and Xi signed a joint statement on cooperation on “linking the construction of the Eurasian Economic Union and the Silk Road Economic Belt”, so far Moscow’s support to BRI has been more of a declaratory character falling short of accession to it. The Chinese side, when it is convenient, mentions Russia as a Belt and Road country, while Moscow simply adheres to the previous formulations.

This may change with Putin’s visit in October, and if so, it could be a historic game changer for the dynamics of Sino-Russian partnership and for the flow of international politics as a whole.

Indian diplomats hope to produce a joint document that papers over the contradictions, which are not only over Ukraine but also climate change, the debt obligations of emerging markets, the Sustainable Development Goals, digital transformation, energy and food security, and so on. The confrontational line of the collective West poses a major obstacle.

The G20 foreign ministers failed to adopt a joint declaration, and the deliberations, under pressure from the G7 countries, “strayed into emotional statements,” as Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov later said. Putin and Xi probably do not expect any breakthrough solutions from the G20 summit.

The strong likelihood is that the forthcoming Delhi event this weekend may turn out to be the last waltz of its kind between the cowboys of the Western world and the increasingly restless Global South. The revival of the anti-colonial struggle in Africa is ominous. Quite obviously, Russia and China are putting their eggs in the BRICS basket.