A container ship at Shenzhen Port, China (File photo)

A container ship at Shenzhen Port, China (File photo)

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s remarks at the 17th ASEAN-India Summit on November 12 makes sad reading. It comes in the specific context of the signing of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership [RCEP] on Sunday — the mega free trade agreement centred on the ASEAN plus China, Japan and South Korea.

Modi avoided mentioning RCEP, although it signifies a joyful occasion in ASEAN’s life as much as Diwali is for an Indian. He instead took detours — ‘Make in India’, ‘Act East Policy’, ‘Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative’, ‘ASEAN centrality’.

India’s policy options toward Southeast Asia, a region it calls “central” to its Act East Policy, have shrunk dramatically. Yet, a recent study by RAND Corporation, the Pentagon think tank, titled Regional Responses to US-China Competition in the Indo-Pacific lists Japan, Australia and India as Washington’s only allies and partners over whom it can confidently claim to have “more diplomatic and military influence than China”.

The RAND analysts drew certain stunning conclusions:

- China has “more economic influence” than US in Asia-Pacific.

- ASEAN countries rank economic considerations over security concerns.

- China can “leverage its economic influence for a variety of goals, including to weaken US military influence.”

- There is “little evidence” that ASEAN countries believe that US “military influence is a counterweight to China’s economic influence.”

- “Concern about US commitment to the region is echoed through Southeast Asia.”

- China has greater leverage than US over the ASEAN countries; and,

- “For Southeast Asia as well as other countries in the Indo-Pacific, there is a strong desire to avoid choosing between the United States and China or appearing to align clearly with one country against the other. We [RAND] expect partner alignment to be weak and incomplete.”

The report bypasses the Donald Trump-Joe Biden binary, which mesmerises Indian analysts and instead underscores that “There is a widespread expectation [among regional countries] that China will overtake the United States as the largest economy in the next ten to 15 years and play a critical role in driving regional economic growth… [The RCEP] would deepen economic ties between the countries involved. There is expectation that trade with China will continue to increase.”

Modi’s sombre remarks echo the angst in the RAND report. The signing of the RCEP is a defining moment. The ASEAN is boarding the RCEP train all set to depart and India is stranded while its two other QUAD partners — Japan and Australia — are on board and can be seen in the dining car holding Chinese chopsticks.

To be sure, this journey will take ASEAN to exotic destinations from where there is no turning back. Modi’s plaintive appeal for a picnic won’t attract the ASEAN as it embarks on an adult relationship of maturity and certitude that India simply cannot offer in an on-again, off-again fling.

For the sake of courtesy, ASEAN has left behind an invite to India to join the RCEP at a time of its choosing, but both sides know that is never to happen.

As the RCEP train picks up momentum, ASEAN will get used to a new lifestyle and begin exploring seamless opportunities to indulge itself. Analysts applaud RCEP as the world’s second most important trade agreement, behind only the World Trade Organization itself.

The saddest part is that in the process, China is also divesting India of its cherished Sinophobic mantras — “a free, open, inclusive and rules-based Indo-Pacific region”; “freedom of navigation and overflight.” Ironically, the RCEP was “free, open and inclusive” but India failed to appreciate that and turned its back on it.

And the RCEP is, without doubt, “rules-based”. It was painstakingly negotiated by fifteen Asia-Pacific countries who held thirty-one rounds of negotiations and eighteen ministerial meetings until they could reach an agreed “text”.

In fact, its principal objective is to harmonise the existing network of “ASEAN+1” FTAs into a unified agreement, creating a single and cohesive set of trade rules for the Indo-Pacific. And it also includes regulatory provisions for many 21st century trade issues, such as services, investment, e-commerce, telecommunications and intellectual property.

Now, these 15 would-be RCEP participant countries account for nearly a third of the global population and approximately thirty percent of global gross domestic product. Measured in terms of trade flow, RCEP’s thirty percent share is only a fraction smaller than the EU Customs Union’s 33% share. RCEP is expected to soon overtake Europe as Indo-Pacific economies rapidly deepen their trade orientation.

Again, RCEP generates such massive maritime traffic once it comes into operation next year that the chanting of “freedom of navigation” in the South China Sea sounds ridiculous. Come to think of it, China is its biggest stakeholder, too!

Take Japan and Australia, India’s QUAD allies. Trade with RCEP member countries accounts for nearly 50 per cent of Japan’s total trade value. The RCEP countries account for 61 per cent of Australia’s total two way trade, and 71 per cent of our exports.

This will be Japan’s first free trade agreement with China and South Korea, which will provide a boost to exports of agricultural and other Japanese products. Australia already has an FTA with China.

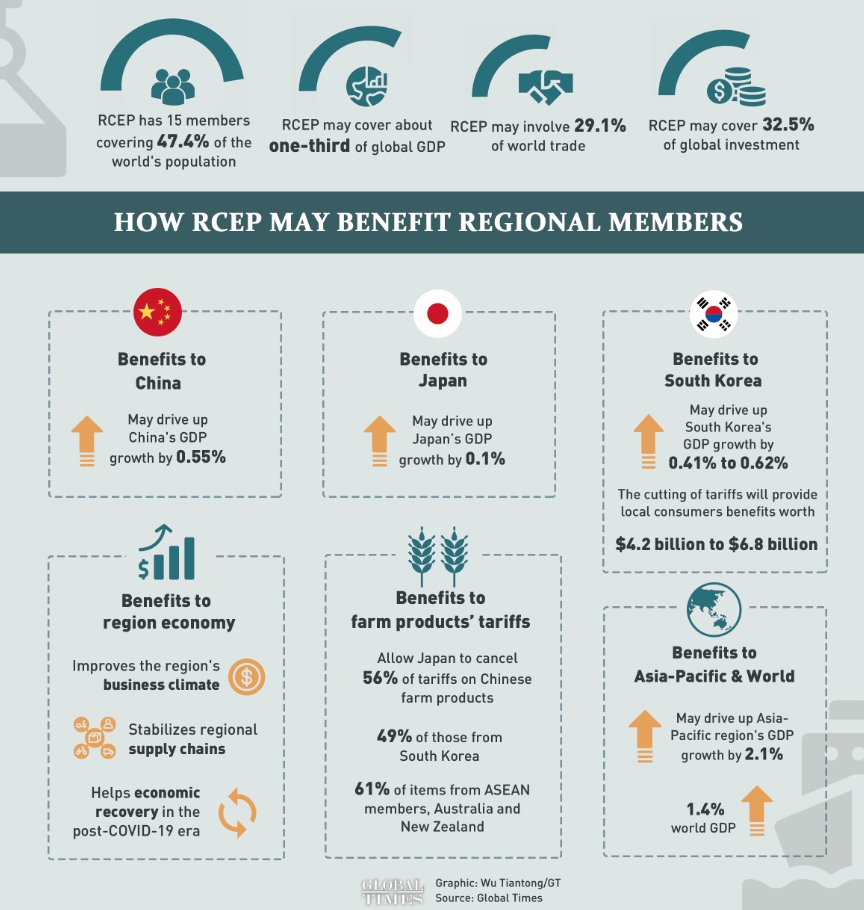

The RCEP will probably abolish tariffs on 61 percent of agricultural imports in ASEAN, 56 percent of those in China, and 49 percent in South Korea. The RCEP is also expected to reduce or remove tariffs on industrial goods such as automobile parts, steel, and chemical products. See the infographic below.

Modi’s remarks signal that the enormity of what is happening in India’s extended neighbourhood is sinking in. The catastrophic mismanagement of the Covid-19 pandemic means that India Inc won’t be open for serious business for quite a while. Meanwhile, RCEP will have begun to remake the economic and strategic map of the Asia-Pacific.

The RCEP matrix based on a single, region-wide set of trade rules will change the economic outlook of its members. The lowering of intra-regional trade and investment will inevitably prompt the RCEP countries to accord higher priority to deepening economic ties among themselves.

To be sure, RCEP heralds the dawn of a new post-Covid regional supply chain. As a new RCEP supply chain takes shape, India has not only excluded itself but is unwittingly facilitating its “arch enemy” China to become the principal driver of growth in the Asia-Pacific.

On the other hand, extra-regional economic ties cease to be a priority for the ASEAN, in relative importance. There isn’t going to be any takers in the Asia-Pacific region for even a partial US-China “decoupling”. The RCEP is in reality an ASEAN-led initiative, which is built on the foundation of the six ASEAN+1 FTAs and it secures ASEAN’s position at the heart of regional economic institutions.

Meanwhile, the RAND report also makes certain incisive assessments regarding the “types of influence” the US has vis-a-vis its QUAD partners. It is with Japan only that the US has the “most diplomatic and political influence across all the indicators.” Australia comes next but Canberra harbours misgivings about US commitment to the Indo-Pacific region, including “increasing worries about US reliability and predictability”.

The RAND gives a qualified welcome for India. It estimates that India sees China as its “most powerful, significant long-term security challenge… In India’s eyes, China is too threatening to be considered a friend but too dangerous to be treated as an overt enemy.” Thus, “China’s military superiority has made Indian planners risk-averse about taking positions that could provoke full-scale warfare.”

Suffice to say, on balance, the RCEP became a non-option for India while QUAD does not become a natural habitat for it, either. Meanwhile, the decision to get into the driver’s seat in the QUAD and raise it to ministerial level was itself heavily predicated on what has turned out to be a deeply flawed assumption — of President Trump securing a second term and Mike Pompeo being around as Modi government’s preferred counterpart in DC.

The strategic dilemma ensuing out of this incredible sequence of diplomatic blunders is writ large on Modi’s remarks. That fire in the belly evident in Modi’s Shangri La speech of June 2018 at Singapore was missing. His ASEAN counterparts would have taken note.