Land-based missile defense system, Aegis Ashore, at the US Navy’s Pacific Missile Range Facility in Kauai, Hawaii. File photo.

Land-based missile defense system, Aegis Ashore, at the US Navy’s Pacific Missile Range Facility in Kauai, Hawaii. File photo.

Regional security in Northeast Asia underwent a jolt on Thursday with the announcement in Tokyo by Japanese Defense Minister Taro Kono that Japan would cancel the purchase of a multi-billion dollar ballistic missile defense system made by Lockheed Martin.

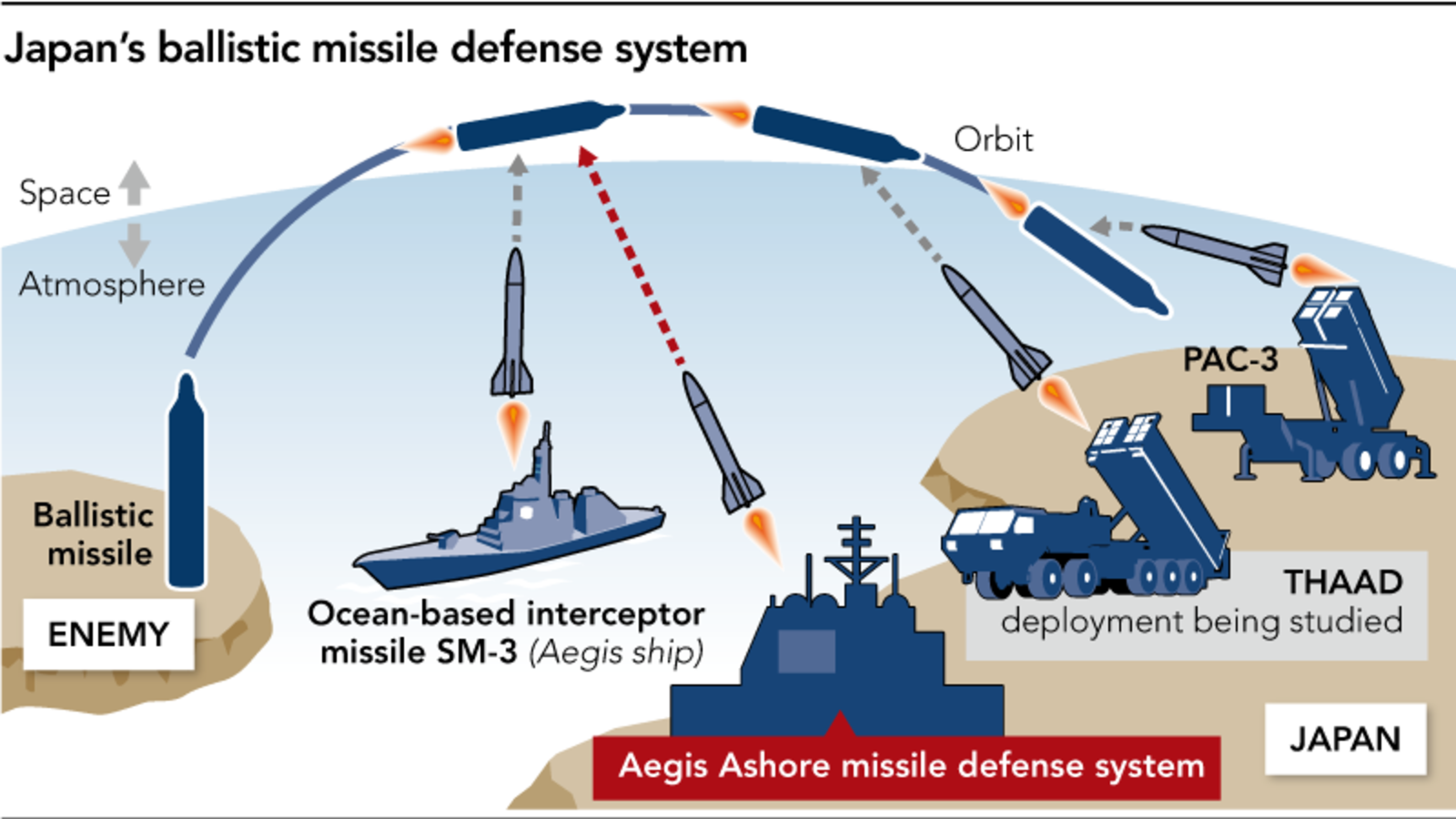

Kano disclosed that the decision to cancel the Aegis Ashore program was taken on the previous Friday by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, which was subsequently approved by the National Security Council on Wednesday. Interceptors for the Aegis Ashore system were to be placed in two regions — Akita and Yamaguchi — under the costly and controversial programme.

The government reversed course under pressure from local residents concerned about the risks posed by a missile defence system in their backyard; due to the high cost of the US missile defence system; and, great reservations expressed by Beijing and Moscow in the recent months.

Japan will now search for a less costly option, including preemptive strike capabilities. Buying more F-35 jet fighters could be one option. The government had originally guaranteed that interceptor missile gear would not land in residential areas near where the system was based. But then, maintaining that promise would have required a costly and time-consuming hardware upgrade.

The Aegis Ashore system, the purchase of which was approved in 2017, was estimated to cost Japan at the very least $4.2 billion over three decades with a strong possibility that initial estimates would fall short of the real cost.

The US president Donald Trump must be an unhappy man since he had boasted about the ABM deal as a mark of his genius to push allies to buy more American products, including military equipment. Abe in turn had projected the deal as part of attempts to bolster defensive capabilities after North Korean missile launches, but in reality, he was also ingratiating himself as a way to foster closer ties with Trump.

Following Trump’s decision to walk out of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty [INF] last August, while putting the blame on Russia, Washington was in reality taking into account the fast-changing military balance in Asia and the steady build-up of China’s conventionally armed missiles.

In the US narrative, China’s growing arsenal of powerful conventionally armed intermediate-range missiles aimed at preventing or constraining the deployment of US forces in the western Pacific.

Admiral Harry B. Harris, then commander of the US Indo-Pacific Command (now ambassador to South Korea), summed up the problem in a testimony before the House of Representatives Armed Services Committee in Washington in April 2017, saying China “controls the largest and most diverse missile force in the world, with an inventory of more than 2,000 ballistic and cruise missiles.” Of those, he added, “Approximately, 95% . . . would violate the INF if China was a signatory.”

Indeed, during the 22 years that the United States and Russia were bound by the terms of the INF, China was actively expanding its own arsenal of intermediate-range missiles, which includes such weaponry as DF-26 and the new DF-17 hypersonic glide vehicle, both with a range of 1,000–4,000 kilometres and with cutting-edge anti-ship ballistic and hypersonic glide technology.

These highly accurate missiles are rated as among the world’s most advanced short- and intermediate-range missiles, forming the core component of a strategy to impede US military activity in the western Pacific. (For a detailed analysis, read the commentary by Carnegie Moscow Centre, What the End of the INF Treaty Means for China, December 2, 2019.)

In the wake of the decision to scrap the INF, the US embarked on an active programme to boost its own arsenal of conventionally armed ground-based intermediate-range missiles by way of the conversion of existing cruise missiles to ground-launched systems and by developing new intermediate-range ballistic missile systems. While the conversion of existing cruise missiles could be completed within 18 months (from testing to deployment), the development of a new ballistic missile system (including development and production of mobile launchers) would take 4-5 years.

Meanwhile, to be within range of Chinese targets, these ground-based intermediate-range missile systems must be deployed somewhere in the western Pacific.

Enter Japan. The point is, no intermediate-range cruise or ballistic missile can be expected to hit a time-sensitive target from a distance of more than 500 kilometres, especially in a pre-emptive strike, which in turn severely constricts deployment choice decisions.

Suffice to say, Japan becomes an ideal partner for the US. A medium-range ballistic missile, takes about 13 minutes to reach a target 2,000 kilometres away. Possible sites for deployment of medium-range ballistic missiles with a range of 750–2,000 kilometres might include Southeast Asia and Japan’s southwest islands.

Suffice to say, Japan becomes an ideal partner for the US. A medium-range ballistic missile, takes about 13 minutes to reach a target 2,000 kilometres away. Possible sites for deployment of medium-range ballistic missiles with a range of 750–2,000 kilometres might include Southeast Asia and Japan’s southwest islands.

China has a network of 40 widely distributed air bases and by some estimates, it would take at least 600 tactical ballistic missiles to effectively disable them. Put differently, it is critically important that Japan and the US work together. But that requires Washington overcoming the political constraints in terms of Japan’s complex relationship of economic interdependency with China, which could be overcome only through a broader and deeper conversation.

In other words, Japan needed to factor in that the forward deployment of US missiles on its soil is bound to intensify China’s suspicion and alarm. Equally, although the US vows that that it does not envision mounting nuclear warheads on the medium-range ground-based missile systems now under consideration, there is always the possibility that in future Washington may simply go ahead and deploy large numbers of “nuclear-capable missiles” if new exigencies arise.

Suffice to say, Japan realises that its relations with China will be in serious jeopardy once it crosses the Rubicon and embraces the US by allowing the latter to deploy intermediate range missiles on its soil.

Beijing and Moscow have made it clear that the deployment in Japan of new US intermediate range missiles directed against them will be regarded as an unfriendly act and there will be serious consequences for which Tokyo will be held responsible. (Incidentally, Moscow has perceptively slowed down its diplomacy aimed at normalising Russo-Japanese relations.)

Even as incipient signs began to appear that Tokyo was having misgivings of its own, Beijing doubled down. At the weekly press briefing in Beijing on Wednesday, the Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Senior Colonel Wu Qian said in reply to a query, “China is firmly opposed to the deployment of intermediate-range missiles by the US in the Asia Pacific region. If the US insists on the deployment, it will be a provocation at China’s doorstep. China will never sit idle and will take all necessary countermeasures.

“At the same time, China hopes that Japan and other countries concerned can act cautiously with the big picture of regional peace and stability in mind, and should not allow the US to deploy medium-range missiles on their territories, so as not to fall victim to Washington’s geopolitical ploys.”

A day later, Defence Minister Kano publicly confirmed to his party colleagues at a meeting in Tokyo that Japan is retracting from its earlier decision. In his words, “The National Security Council discussed this matter and reached a conclusion that the deployment of Aegis Ashore in Akita and Yamaguchi is to be rescinded. I want to deeply apologise that it has come to this.”

Apart from growing domestic opposition, against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic and Japan’s prioritisation of economic recovery in the post-pandemic era, Tokyo would have concluded that this is not the time to provoke China and Russia with an anti-missile defense system, which could trigger an arms race in the region. Kono admitted, “Our understanding of the matter was naïve.”

Tokyo’s decision would have negative implications for Japan-US relationship but would have positive fallouts for the security patterns in Northeast Asia.

Abe has been proactively expanding imports from the US, boosting investments in the US while purchasing large quantities of American weapons, including Aegis Ashore and fighter jets, to offset deficits with the US and keep the relationship relatively stable. But the sudden suspension of Aegis Ashore deployments will impact the US-Japan security alliance. No doubt, Trump loses face.

The deployment of the Aegis Ashore as part of its strategic deployment in the Asia-Pacific region would have boosted the US capability to monitor China and Russia. Therefore, Japan’s suspension also highlights the US’ diminishing influence over its allies. It optics are that the US has a problem to convince regional states to join its anti-China bandwagon.

2020 marks the 60th anniversary of the signing of the US-Japan Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security. The security alliance will not collapse any time soon, but its intimacy is wearing off. It is no longer the case that Japan would sacrifice its interests to comply with US demands. As a Chinese scholar noted recently, “Japan is no longer the little brother of the US acting at Washington’s beck and call.”