Arakan Army troops pose in front of the Central Navy Seal Training Center after seizing it, Rakhine, Myanmar, Sept 5, 2024

Arakan Army troops pose in front of the Central Navy Seal Training Center after seizing it, Rakhine, Myanmar, Sept 5, 2024

The sharp escalation by the Kuki militants in Manipur has shaken up the Indian establishment but the ensuing jingoistic outcry in sections of the media demands a muscular approach to addressing the problem of militancy. This is fraught with serious consequences.

The editorial comment by a prominent Indian newspaper puts the government’s dilemma in perspective: “Some positive gestures need to be made to settle the ethnic conflict, but [Chief Minister] Singh is totally opposed to the Kuki demand of autonomous administration. He ought to realise that Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s advice to Russia and Ukraine that peace does not come from the battlefield, but through dialogue, applies to Manipur as well.”

Coincidence or not, in next-door Myanmar, Delhi is getting a preview of what happens when dialogue is not the preferred course to conflict resolution.

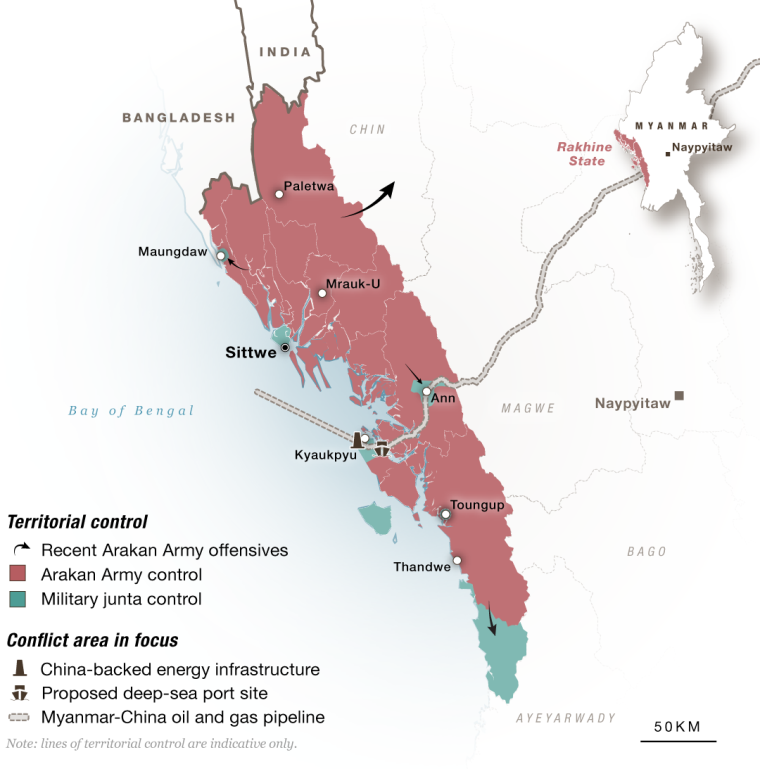

Last Thursday, the ethnic Arakan Army [AA] announced that it has seized the Navy Seal Training Center in southern Rakhine State after a month of intense fighting, overcoming resistance by government forces backed by Navy ships and aircraft.

The AA cadres now control territories on the borders with Bangladesh, including towns such as Buthidaung and is threatening other important port cities/towns on the Bay of Bengal coastline such as Kyauk Phyu, Sittwe.

Arkan is a highly strategic region. Oil and gas pipelines run from Kyauk Phyu to China’s Yunnan province; Kyauk Phyu is also a vital node in China’s Belt and Road Initiative, with proposals to expand the deep sea port and other related investments. Peace and stability in Sittwe is critical for the success of India’s Kaladan project, which seeks to connect Kolkata with Mizoram via Myanmar.

The Arakan army may emerge as one of the key players in defining the regional security dynamic of the Bay of Bengal with its ability to impact the implementation of various infrastructure projects and the trajectory of the Rohingya crisis.

So far, the Ethnic Armed Organisations and resistance groups such as the People’s Defence Forces supported by western intelligence agencies have refrained from declaring independence of territories under their control but this is to be understood as a tactical decision for the present.

Like in India’s northeast region, the ethnic geographies in Myanmar are complex. Given considerable movement of people internally through decades, there are no ‘pure’ ethnic homelands. Many geographies are multi-ethnic, and members of various ethnic groups often share urban spaces in towns and cities.

Inevitably, the boundaries of homelands will be hotly contested, which will generate considerable inter-ethnic friction. Overall, with multiple armed groups contesting for and asserting power in different regions, Myanmar has become a space with fragmented sovereignty.

AA is a Buddhist ethnic group and Rakhine communities exist in India also. Historically, Arakan which was an independent kingdom, was conquered by Burma in 1784 but ceded to British India as war reparation just 42 years later after the First Anglo-Burmese War. However, in 1937, Arakan was made a Crown Colony of British Burma, split off from British India. The communal strife between majority Arakanese and Muslim communities dates back to the colonial era following the mass migration from present-day Bangladesh.

Sinophobic Indian commentators are intentionally or unwittingly projecting a conflict of security interests between India and China. (Some analysts have eve conjured up from thin air a Chinese hand in the recent regime change in Bangladesh.) There is no empirical evidence pointing toward China fuelling the insurgent groups in India’s northeast region.

China’s response to Myanmar has been to engage with multiple actors, given the huge stakes in its investments and economic interests as well as security concerns over criminal syndicates operating in Myanmar’s lawless borderlands. China’s primary worry is that Myanmar may descend into complete chaos with the military’s disintegration.

Thus, China keeps substantive relations with many armed groups, especially the United Wa State Army (UWSA) and the Three Brotherhood Alliance (of which AA is a constituent.) Interestingly, China visualises UWSA as a factor of border security and stability and has even allowed it to procure commercial drones from the Chinese market and use them in their operations against the military, while, conceivably, UWSA also becomes a conduit through which Chinese arms would reach other rebel ethnic groups.

However, all this does not preclude China from also ensuring a steady supply of defence equipment to Myanmar’s military. According to a UN report released this month, China has supplied ‘fighter aircraft, missile technology, naval equipment and other dual-use military equipment’ to Myanmar in the past two years.

Arguably, there is a congruence of interests between China, India and ASEAN in engaging with the central authorities in Naypyidaw for the stabilisation of Myanmar. But it is only China that is proactive. India has episodic interaction with ASEAN, none at all with China and focuses almost entirely on engagement with the Myanmar military leadership.

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit to Naypyitaw on August 14 aimed at giving a new push to resolve Myanmar’s crisis. Two days later, at a meeting on the sidelines of the Mekong-Lancang Cooperation Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in Chiang Mai, Wang presented a 3-point approach before with his counterparts from Laos, Myanmar and Thailand that China: “Myanmar should not be subject to civil strife; should not be detached from the ASEAN family; and, should not be allowed to be infiltrated and interfered with by external forces.”

Four days later, Wang met with UN special envoy for Myanmar Julie Bishop in Beijing, where he affirmed China’s commitment to a “Myanmar-owned, Myanmar-led” peace process. On the same day, the Southern Command of the People’s Liberation Army announced the successful conclusion of live-fire drills on China’s border with Myanmar.

In the evolving situation, the regime change in Bangladesh is potentially a game changer. It is a matter of time before the new compradore regime in Dhaka jumps into the fray, abandoning Hasina’s policy of non-interference in Myanmar’s internal affairs. Carving out a proto-state in Rakhine along the highly strategic Bay of Bengal coastline as a cockpit of western interests is a distinct possibility.

Bangladesh already has a proposal on the table with the support of the International Committee of the Red Cross to secure three areas in Rakhine, home to the Rohingya Muslim community who constitute 35% of the population, suggesting that people displaced by the violence be relocated (close to a million people) there under the supervision of an international organisation, such as the United Nations.

The AA, one of Myanmar’s most powerful armed groups, is opposed to the idea. In Rakhine’s north, AA is already embroiled in a complex three-way battle that also involves Rohingya Muslims. AA’s modest goal is to create an autonomous enclave for the Buddhist population who comprise 65% of Rakhine’s population.

The AA presently holds nine entire townships in the centre and north, as well as much of the Bangladesh border. It could soon take Sittwe, the state capital, as well as the military’s regional command headquarters farther south. AA is extremely popular among Rakhine people. There is a looming danger of a brutal war pitting the Buddhist Rakhine against the Muslim Rohingya in which external powers are sure to get involved.

In a statement, the Brussels-based think tank International Crisis Group estimated in May that from the refugee camps in Bangladesh, “in recent months thousands of would-be fighters have crossed the border into Myanmar… (and) the recruitment campaign has escalated dramatically in recent days… Bangladeshi law enforcement agencies have done little to stop this.” This was while Hasina was in power.