(Mahinda Rajapaksa)

India has done the right thing by keeping a line open to the newly appointed Sri Lankan prime minister Mahinda Rajapaksa. It is not in India’s interests to lend credence to the western narrative of Rajapaksa being “pro-China”.

The well-known public figure and BJP parliamentarian Subrahmanyam Swamy who hosted Rajapaksa in Delhi in September recently described the Sri Lankan leader as first and last a “staunch nationalist” and expressed confidence that his re-emergence at the leadership level can work to India’s advantage. So long as our policymakers understand this home truth, a smooth adjustment to the emergent realities in Sri Lanka becomes possible.

Fundamentally, India needs to be mindful of the famous axiom by Charles de Gaulle that “no nation has friends, only interests.” China follows it – be it in Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka or the Maldives. Why can’t India do the same?

Our main problem could be that the China bogey comes handy to our security establishment whenever its hare-brained schemes in the neighboring countries crash land. Second, there are foreign powers – the US, UK, Australia, etc. – who somehow want to establish India-China rivalry to be the leitmotif of the geopolitics of the South Asian and Indian Ocean region, as a means to leverage India’s foreign and security policies. Alas, sections of the Indian academia, ‘think tanks’ and the media are also open to manipulation.

However, the good part is that as Swamy’s remark shows, there is a growing appreciation of Rajapaksa among the ruling elite. A Reuters report quoted the well-known RSS leader Seshadri Chari as expressing confidence that Delhi can do even better business with Colombo under the new leadership in Sri Lanka.

Chari was spot on when he told Reuters, “In the changed geo-political realities, we have to be practical and pragmatic to protect our national self-interest and do better business.” This is indeed the crux of the matter.

This is indeed the spirit in which we must pick up the threads of Delhi’s equations with the new dispensation in Colombo. Delhi knows only too well that Sri Lanka has a robust democratic tradition (which is only to be expected in a country with one hundred percent literacy.) What follows is that Sri Lankan party politics is extraordinarily animated. (In fact, the schism between the two main parties – UNP and SLFP – goes back in time by several decades to the 1950s.)

As in any democratically elected leadership, the politicians in Colombo who lead governments also feel the need of accountability and the compulsions to nurture their political constituencies. We should not malign them as vassals of foreign powers. Take Ranil Wickremesinghe. He has a solid record of being a ‘westernist’ by way of his family and social background, upbringing, mindset, political ideology – as most urbane UNP leaders before him also have been, especially his uncle and former president JR Jayewardene. But did that prevent Wickremesinghe from turning to China for financial help when his government was strapped for cash? The plain truth is that China could expand its business interests further in Sri Lanka during his period in power since 2015.

In retrospect, the decision makers in South Block took an appalling decision when they turned down Rajapaksa’s initial request for Indian help to develop Hambantota Port (which is located in a region that forms his power base in the deep south of Sri Lanka.) The advice our mandarins proferred to him was apparently that Sri Lanka didn’t need such a port!

(Hambantota Port)

But Rajapaksa was determined to have such a project in the Sinhala heartland and approached Beijing for help. The rest is history. Again, do we realize that Rajapaksa can be a stakeholder in getting the Mattala international airport running as early as possible?

(Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport)

If we approach the paradigm with imagination and sensitivity (instead of wallowing in Sinophobia), we have excellent prospects for securing the management contract of the airport. In fact, the project can be a money-spinner, too.

The point is, the airport is virtually a “feeder” – some 30-40 minutes away by the expressway – for the Hambantota Port and the adjacent industrial zone that China is developing. Now, Mattala is also a region whose development is a priority for Rajapaksa.

And above all, China has hinted fairly explicitly several times – including in a commentary in the Chinese tabloid Global Times this week – that an Indian management of Mattala Port is just what the doctor prescribed – “China-India plus one”.

Similar opportunities are arising also with regard to another controversial Rajapaksa legacy – the Chinese project in Colombo Port, where actually 80 percent of commercial activity is expected to be stemming from trans-shipment to and from India’s string of feeder ports along the west and east coast.

(Colombo Port City under development)

This, again, can be approached in the spirit of “China-India plus one”. But the bottom line is that we really need to dump our mindset brimming with hubris and prejudices.

Politicians like Rajapaksa are mass leaders who have come through the rough and tumble of Sri Lankan politics – which is an extremely tough turf, by the way. They are not going to sell their country down the drain to any foreign power. They are very possessive about their country’s national sovereignty, independence and strategic autonomy.

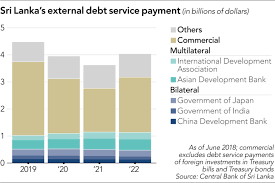

Fact check is alien to the culture of Indian strategic discourses. Or else, we wouldn’t have rushed into phoney notions that China has got Sri Lanka entangled in a “debt trap” because of Rajapaksa. In reality, China figures as the least of all problems amongst Colombo’s debt service payments.

A China hand in JNU has been quoted as saying in the Reuters report (commenting on Rajapaksa’s return to centre stage: “It’s advantage China at the moment”. This is baloney. Such opinions can only help the security establishment get off the hook for its historic blunder of dabbling in Sinhala party politics as if it is an adjunct to Indian state politics – splitting Sinhala parties and knocking the heads of Sinhala politicians against each other.

Given the rethink on Rajapaksa, as evident in the remarks by Swamy and Chari, I see the hopeful sign that the developments in Colombo can turn into “advantage India” – provided of course we see the emerging situation exclusively through the prism of Indian interests. Make no mistake, Rajapaksa will be interested in optimally exploring “China-India plus one.”