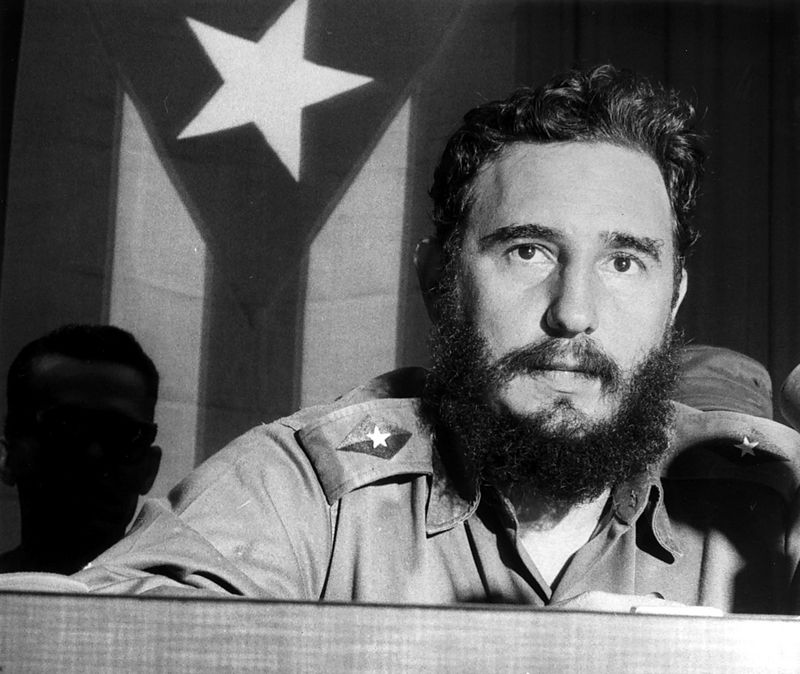

A US Senate commission in 1975 counted eight assassination attempts by CIA agents on Fidel Castro during 1960-1965

A US Senate commission in 1975 counted eight assassination attempts by CIA agents on Fidel Castro during 1960-1965

In the Russian journal Natsionalnaya Oborona (National Defence), the chief of Russia’s foreign intelligence Sergey Naryshkin has written a riveting essay on the 75th anniversary of the Central Intelligence Agency, which falls on Sunday. It is an unusual gesture, especially in the middle of the hybrid war in Ukraine.

Probably, it serves a purpose? Most certainly, it serves to remind the Russian people and foreigners alike that nothing has been forgotten, nothing forgiven.

The title of the essay — 75 candles on the CIA Cake — is somewhat misleading, as Naryshkin’s concluding remark is that “Anniversary congratulations and wishes there will not be. As there can be no compromise in assessing its (CIA’s) role in history and ‘merits’ to humanity.”

Naryshkin’s essay will be closely studied by the western intelligence for any “clues.” Indeed, what is he messaging? Naryshkin and President Vladimir Putin go back some 40 years. Naryshkin had just graduated from one of Moscow’s most prestigious institutions, the Felix Dzerzhinsky Higher School of the KGB and Putin was already working in the foreign intelligence department of the Leningrad KGB when they bumped into each other in the corridors of the Big House (as KGB’s regional headquarters in Leningrad was known).

Unsurprisingly, Naryshkin writes about the CIA with an easy familiarity. As he put it, “The CIA was created at the beginning of the Cold War era in order to conduct intelligence activities around the world as a tool to counteract the existence and strengthening role of the USSR in the world, the formation of a bloc of socialist states, and the rise of the national liberation movement in Africa, Asia, and South America.”

Funnily enough, nonetheless, the CIA began with a colossal intelligence failure when it predicted on 20th September 1949 that the first Soviet atomic bomb would appear in mid-1953, when, actually, 22 days before the publication of that forecast, the Soviet Union had already conducted its first test of a nuclear device.

The CIA was once again clueless when Putin announced in March 2018 in an address to the Russian Parliament that Russia had developed a new hypersonic missile system, which “will be practically invulnerable.” US officials and analysts were taken aback. The CIA has a history of getting Russia all wrong, including about the collapse of the Soviet Union.

But the CIA had its successes too — for example, the overthrow of Iran’s democratically elected prime minister Mohammed Mossadegh in 1951 after his move to nationalise Iranian oil fields. By the 1950s, CIA already turned into a “multi-disciplinary monster” when besides traditional intelligence activities, it was also “tasked with tracking and suppressing any political, economic, military processes in all parts of the planet that could threaten the world hegemony of the United States and its allies.” Naryshkin gives credit to Allen Dulles for this metamorphosis. Dulles introduced “aggressiveness and lack of morality into the activities” of the CIA. He was just the man to do so, having been station chief of the OSS (CIA’s predecessor) in Bern in 1942-1945, who had clandestine dealings with the Nazis behind the back of the US’ Soviet ally.

Naryshkin takes us through the chronicle of CIA’s “coups d’etat, direct military interventions, provocations of all kinds, assassinations of objectionable politicians, terror, sabotage, bribery” and all that cloak and dagger stuff, which prompted President Lyndon Johnson’s famous condemnation of the agency as the “damn murder corporation.” Like in Banquo’s ghost scene at Macbeth’s banquet table in Shakespeare’s play, the victims appear — Patrice Lumumba, Salvador Allende …

There are chilling references to the CIA’s practice of using cancer spreading technology to eliminate “objectionable” Latin American leaders — Argentina’s Kirchner (thyroid cancer), Paraguay’s Lugo (lymphoma), Brazil’s Lula da Silva (laryngeal cancer) and D. Dilma Rousseff (lymphoma) — and, of course, Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez (tracheal cancer). According to Naryshkin, “In 1955, the CIA attempted to eliminate Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, who was perceived by the Americans as “a maniacal fanatic seeking to take over the world,” but failed miserably. Agents blew up the plane on which Zhou was supposed to fly to a conference of Asian and African leaders in Indonesia.” Thereupon, Dulles developed a plan to poison Zhou but gave up fearing that CIA’s involvement might get exposed!

A US Senate commission in 1975 uncovered and confirmed CIA involvement in contract killings and coup d’état. It counted 8 cases of assassination attempts by CIA agents and mercenaries on Fidel Castro during 1960-1965 alone. Havana later revealed the full tally — from 1959 through 1990, CIA planned 634 assassination attempts on Fidel. To quote Naryshkin, “With maniacal persistence, the CIA officers developed simply exotic ways to eliminate the Comandante. They tried to kill him with the help of suicide pilots, paratrooper agents, recruited agents from the inner circle, shelling cars and yachts from ships, boats and subversive saboteurs, with the help of scuba gear with a tubercle bacillus brought there, poisoned cigars, poisonous pills for food and much more.”

“The CIA used every opportunity to inflict maximum damage on the Soviet Union, including economic damage. CIA director W. Casey personally addressed the king of Saudi Arabia and persuaded him to sharply increase oil production, which caused world prices for the most important export resources for the USSR to fall by almost three times. For the budget of the Soviet Union, this was a huge loss, which seriously influenced further political events in the USSR.”

Naryshkin throws some riveting insights into the saga of Ukraine in the 1948-1949 period when the CIA “actively used the experience of Hitler’s special services for launching subversive work against the USSR with recruits in the camps of displaced East Europeans who included quarter of a million Ukrainians. “Almost all the leaders and top functionaries of the Ukrainian nationalists were in one way or another bound by cooperation with the Nazis and therefore were completely controlled” by the CIA and British intelligence. In November 1950, the head of the CIA’s Policy Coordination Office, Frank Wisner bragged that CIA was capable of deploying up to 100,000 Ukrainian nationalists in case of a war with the Soviet Union.

The U2 incident — shooting down the CIA spy plane — in the Urals on May 1, 1960 was a dramatic incident when Washington accused the USSR of destroying a scientific aircraft and a pilot-scientist, but was profoundly embarrassed when Moscow presented not only the wreckage of the aircraft and spy equipment to the media, “but also the living pilot Francis Gary Powers, who frankly told what he was doing in the sky over the USSR and on whose instructions.”

On the other hand, the masterstroke of a South Korean Boeing entering Soviet airspace and getting shot down in 1983 provided just the “propaganda basis” for President Reagan “to announce another ‘crusade against communism.’ The policy of detente was thrown aside, and a new round of the arms race began.”

Naryshkin’s final reflection is calm and collected with no trace of hyperbole: “Evaluation of the effectiveness of any special service is always relative. The US Central Intelligence Agency, entering its 76th year of existence, has been and remains a zealous executor of the will of the ruling circles of its country. Despite the significant changes taking place, they continue to imagine themselves as the only hegemon in the unipolar world. The organisation is intelligence, based on its name, but with a sensitive focus on conducting subversive actions against sovereign states.”

To Indians, CIA has become a benign creature, no longer feared. Having links with the CIA carries no stigma among Indian elites. They regard “CIA phobia” as a legacy of the Indira Gandhi era. And they can be thriving as mainstream columnists and think tankers — and opinion makers. Naryshkin’s essay is a sobering reminder that history has not ended — and it never will.

The essay (in Russian) is here.