Remote land and people of the Russian Arctic

Remote land and people of the Russian Arctic

The Biden Administration’s efforts to put on fast track Sweden’s accession as a NATO member petered out as Turkiye balked, exercising its prerogative to withhold approval unless its conditions regarding Stockholm’s past dalliance with Kurdish separatist elements is fully addressed.

President Biden was bullish and insisted publicly that Sweden’s NATO membership was a foregone conclusion. He underestimated President Recep Erdogan’s tenacity and overlooked the geopolitical ramifications.

Biden and NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg assumed that all that was needed was a face-saving formula to pander Erdogan’s vanity — ie., a few Kurdish militants in Sweden would be extradited and Ankara and Stockholm would thereupon kiss and make up.

However, as time passed, Erdogan kept shifting the goal post and refined his conditions to include issues such as Sweden lifting its arms embargo against Turkiye, joining Ankara’s fight against banned Kurdish militants as well as extradition of people linked to US-based Muslim cleric Fethullah Gulen whom Turkish government accuses of masterminding the 2016 failed coup attempt, reportedly with American backing.

Evidently, Swedes didn’t realise that Turkiye had such deep knowledge of the covert activities of their intelligence.

To cut the story short, Swedish Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson finally took the exit route saying on Sunday in exasperation that “Turkey has confirmed that we have done what we said we would do, but it also says that it wants things that we can’t, that we don’t want to, give it.”

“We are convinced that Turkey will make a decision, we just don’t know when,” he said, adding that it will depend on internal politics inside Turkey as well as “Sweden’s capacity to show its seriousness.”

Stoltenberg has reacted stoically, saying, “I am confident that Sweden will become a member of NATO. I do not want to give a precise date for when that happens. So far, it has been a rare, unusual and fast membership process. Normally, it takes several years.”

Meanwhile, Sweden’s defence ministry announced on Monday that negotiations have begun for a bilateral security pact with Washington — so-called Defense Cooperation Agreement — which makes it possible for American troops to operate in Sweden.

As Defence Minister Pal Jonson put it, “It could entail storage of military supplies, investments in infrastructure to enable support and the legal status of American troops in Sweden. The negotiations are started because Sweden is on its way of becoming an ally of the United States, through the NATO membership.

That is to say, the US is no longer waiting for the formalisation of Sweden’s accession as a NATO member but will simply assume it is a de facto NATO ally!

A press release on Monday by US state department said the bilateral security pact will “deepen our close security partnership, enhance our cooperation in multilateral security operations, and, together, strengthen transatlantic security.” It referred to US commitment to “strengthening and reinvigorating America’s partnerships to meet common security challenges while protecting shared interests and values.”

The crux of the matter is that a security will provide the necessary underpinning for a US deployment to Sweden on an immediate basis, which is not possible otherwise without Stockholm formally jettisoning its decades-old policy of military non-alignment.

This ingenuous route signifies a monumental shift for Sweden which has a long history of wartime neutrality. Put differently, Russia strongly opposes Sweden’s NATO membership, but Washington is reaching its objective anyway.

Interestingly, though, Finland, which also had thrown its hand in the NATO ring under US pressure, doesn’t seem to be in a tearing hurry to negotiate a pact with Washington, although it has a 1,340km border with Russia. Finland’s stance is that it would join NATO at the same time as Sweden.

Foreign minister Pekka Haavisto told reporters on Sunday, “Finland is not in such a rush to join NATO that we can’t wait until Sweden gets the green light.” A former Finnish President Tarja Halonen once said, Finland and Sweden are “sisters but not twins.” They have commonalities, but their motivations are not the same.

Unlike Sweden which was all along in the Western orbit and provided secret intelligence to Western powers throughout the Cold War, both bilaterally and through NATO, Finland had a unique relationship with Russia, which was a result of its history.

Finland positioned itself as a neutral country during the Cold War maintaining good relations with the Soviet Union, riveted on the doctrine enabled by the Agreement of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance (1948) with Moscow, which served well as the main instrument in Finnish-Soviet relations all the way until 1992 when the Soviet Union got disbanded.

For sure, the 1948 pact granted Finland enough freedom to become a prosperous democracy, while, in comparison, despite Sweden’s public posture of neutrality throughout much of the Cold War, behind closed doors it had become a key partner of NATO in Northern Europe.

Conceivably, neutrality still could remain an appealing alternative for Finland. Of course, it is a different matter if the balance of power in the region changes dramatically in the event of a large-scale conflict in Europe.

Sweden’s (or Finland’s) NATO membership isn’t exactly round the corner. Sweden is either unable or unwilling to fulfil Turkiye’s demands. Besides, there are variables at work here.

Most important, the trajectory of the current Russian-brokered rapprochement between Ankara and Damascus will profoundly impact the fate of the Kurdish groups in the region — and the Kurdish-US axis in Syria. Washington has warned Erdogan against seeking rapprochement with President Bashar Al-Assad.

What complicates matters further is that presidential and parliamentary elections are due in Turkiye in June and Erdogan’s political compass is set. Any change in his calculus can only happen in the second half of 2023 at the earliest.

Now, 6 months is a long time in West Asian politics. Meanwhile, the Ukraine war will also have phenomenally changed by summer.

Finland is ready to wait till summer, but Sweden (and the US) cannot. The heart of the matter is that Sweden’s NATO membership is not really about the war in Ukraine but is about containing the Russian presence and strategy in the Arctic and North Pole. There is a massive economic dimension to it, too.

Thanks to climate change, the Arctic is increasingly becoming a navigable sea route. The expert opinion is that nations bordering the Arctic (eg., Sweden) will have an enormous stake in who has access to and control of the resources of this energy- and mineral-rich region as well as the new sea routes for global commerce the melt-off is creating.

It is estimated that forty-three of the nearly 60 large oil and natural-gas fields that have been discovered in the Arctic are in Russian territory, while eleven are in Canada, six in Alaska [US] and one in Norway. Simply put, the spectre that is haunting the US is: “The Arctic is Russian.”

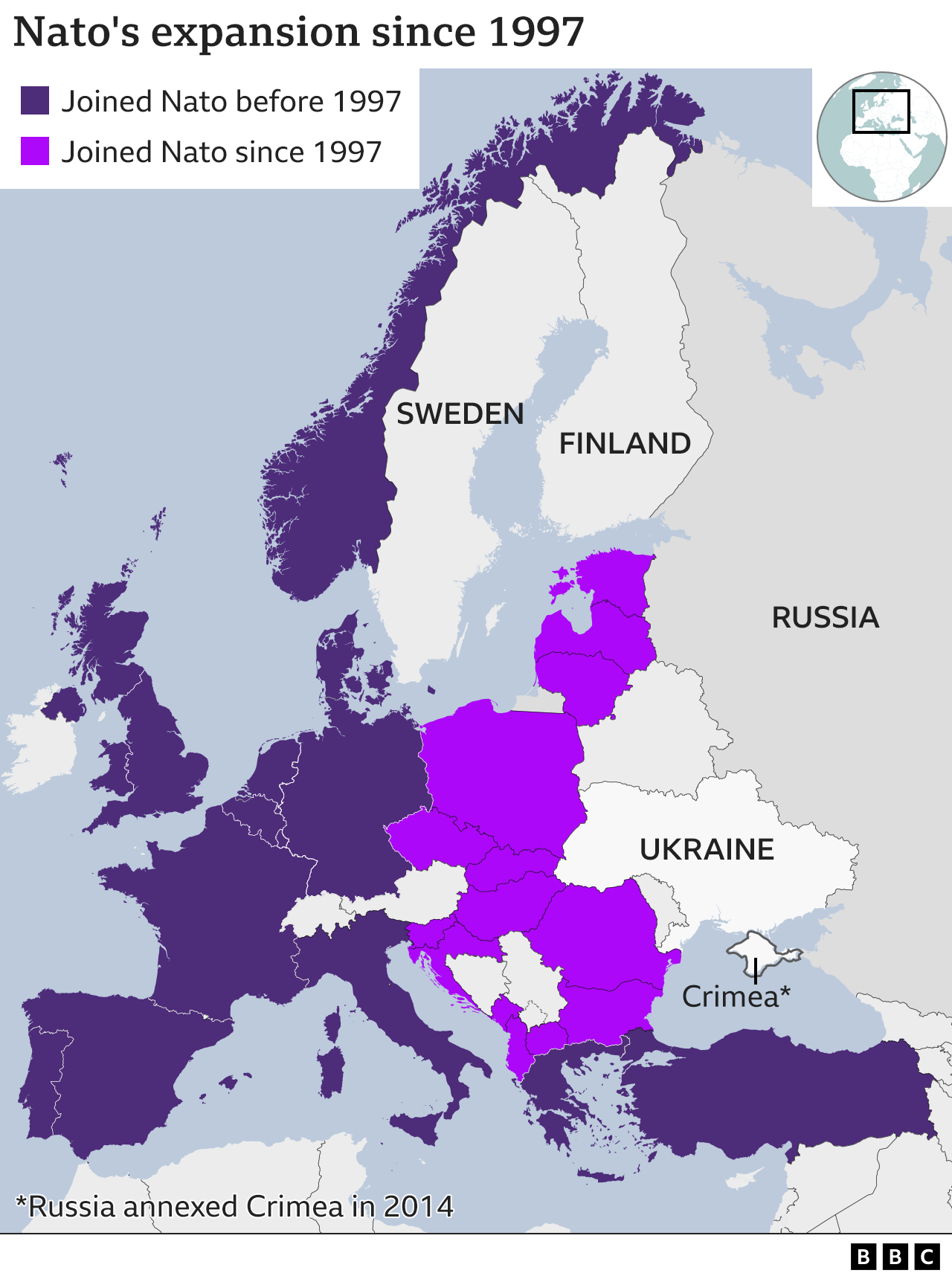

Just look at the map above. Sweden can bring quite a bit to the table to secure the Arctic through NATO. Finland may have a strong icebreaker-ship building industry, but it is Sweden’s highly effective submarine fleet that will be crucial — both for polar defence and for blocking Russia’s access to the world oceans.

Just look at the map above. Sweden can bring quite a bit to the table to secure the Arctic through NATO. Finland may have a strong icebreaker-ship building industry, but it is Sweden’s highly effective submarine fleet that will be crucial — both for polar defence and for blocking Russia’s access to the world oceans.