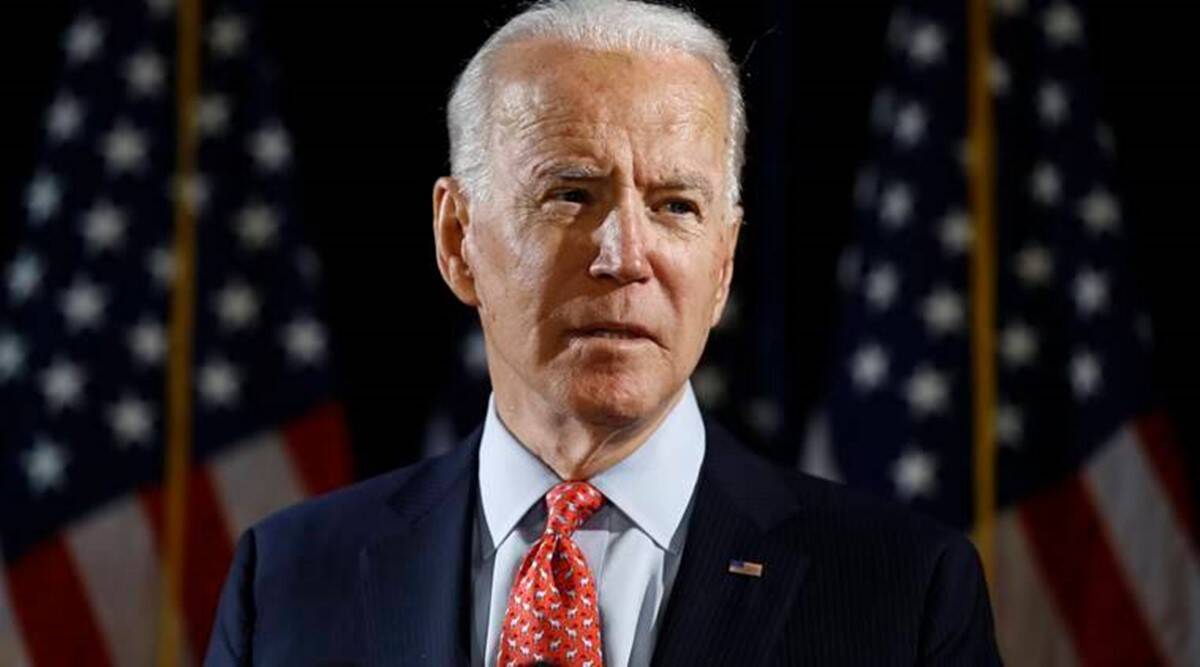

In a sudden change of heart, US President Biden may relent to lift the ban on export of raw materials for India’s Covid vaccine.

In a sudden change of heart, US President Biden may relent to lift the ban on export of raw materials for India’s Covid vaccine.

In the coming week, the commander of the US Central Command Gen Kenneth F. McKenzie Jr. is expected to provide Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin with options for potential future counterterrorism operations in Afghanistan. During a hearing at the US House Armed Services Committee Tuesday, McKenzie indicated that many issues are still being figured out by the administration.

Given the high sensitivity involved, McKenzie offered to dilate on them in closed-door briefings with lawmakers, but he and other witnesses made the following open remarks:

- Biden Administration is “further planning now for continued counterterrorism operations from within the region.”

- Pentagon is considering “how to continue to apply pressure with respect to potential [counterterrorism] threats emanating from Afghanistan. So, [we are] looking throughout the region in terms of over-the-horizon opportunities.”

- US diplomats will be talking to countries in the region where the US could potentially base resources that it could use to conduct operations in Afghanistan. These basing agreements would allow the US to legally station their soldiers in another country, and, depending on the terms of the agreement, conduct either surveillance or kinetic operations.

- US is seeking more opportunities for “expeditionary basing” in the region. US might not seek permanent bases due to Iran’s proximity.

- Although the US military was leaving, “we will keep providing assistance to the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces.” (Emphasis added.)

All of the above issues will be worth watching in the coming months. From the Indian perspective, what matters most is Delhi’s involvement, if any, in the US’ basing arrangements in the region. The US has a logistics agreement with India, which could facilitate mission-based deployments in Indian bases.

On April 16, the Afghan National Security Advisor Hamdullah Mohib had briefed his Indian counterpart Ajit Doval about “what should happen as we prepare for this dialogue (on the transition in Afghanistan with the US and NATO).” This was immediately after the daylong visit to Kabul by the Secretary of State Antony Blinken. India’s role presumably figured in Blinken’s talks in Kabul.

On April 19, Blinken himself had a call with EAM S. Jaishankar when they reaffirmed “the importance of the US-India relationship and cooperation on regional security issues” and “agreed to close and frequent coordination in support of a lasting peace and development for the people of Afghanistan.”

Washington has a long diplomatic history of transactional relationships. Currently, the US-Indian relationship is under duress due to one particular ‘non-transaction’ — the Biden Administration’s apparent unwillingness to lift the ban on raw materials for the manufacture of Covid-19 vaccines in India. The Biden Administration has been sitting tight.

That is, until April 24, when, in a mood softening, Blinken and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan suddenly took recourse to megaphone diplomacy. Blinken tweeted,“Our hearts go out to the Indian people… We are working closely with our partners in the Indian government, and we will rapidly deploy additional support.” Sullivan was candid: “We are working around the clock to deploy more supplies and support to our friends and partners in India as they bravely battle this pandemic. More very soon.”

This is an overnight turnaround. Just the day before, the state department spokesmen had stonewalled, maintaining with a straight face that America’s needs took priority. What prompted this turnaround is unclear. One reason could be the Chinese offer to help India, which Delhi promptly began considering.

However, the bottomline is that Washington almost always expects a quid pro quo in its transactional relationships. Conceivably, Afghanistan could be the quid pro quo, since vital US interests are at stake, including the prestige of the Biden presidency.

Now, McKenzie had disclosed that US diplomats were pulling all stops to firm up the basing arrangements for Afghan operations and based on their inputs, he’d develop options by next weekend. Aside India, Blinken has consulted the Central Asian countries. He spoke to his Kazakh and Uzbek counterparts and took a meeting of the so-called ‘C5+1’ (exclusive format of the US and the five ‘Stans’) where Afghanistan was the leitmotif (here, here and here.)

However, unlike in 2001 when Moscow helped to secure the access to Central Asian bases for the US military to launch its operations in Afghanistan in the downstream of the 9/11 attacks, this time around, the US-Russia tensions are escalating toward open hostility. In an extraordinary piece on Friday, former Russian president Dmitry Medvedev voiced the Kremlin’s stark warning to Biden that “relations between Russia and the US have shifted from competitiveness to confrontation, effectively going back to the Cold War era” and this is “plunging the world into a state of permanent instability.”

A report in the US-funded RFERL seemed despondent that the Central Asian states may not get associated with the Pentagon and CIA’s future operations in Afghanistan. Wherever the CIA goes in the post-Soviet space, the virus of ‘colour revolution’ spreads and the Central Asian regimes must be wary of it. Belarus’ current experience is a stark reminder.

Besides, the major regional states — Russia, China, Iran and Pakistan — would disfavour any spillover of the Afghan conflict into Central Asia. A massive Russian-Tajik military exercise on April 19-24 involving 50000 troops underscored that Moscow views the US intentions in Afghanistan with disquiet.

Thus, India would probably be the only remaining regional state in Washington’s consideration zone today as a potential collaborator. No doubt, the US is in desperate hurry as the troop withdrawal from Afghanistan has commenced. The big question is whether the US is relenting on the vaccine front with a view to cut a deal with India on Afghanistan.

The very thought of it, of course, is very frightening. But if past experience is any guide, Washington has shown savviness to exploit India’s travails. A big step recently toward institutionalising the QUAD was possible only due to India’s border tensions with China.

However, Afghanistan is a ‘graveyard of empires.’ The calculus of fratricidal wars keeps changing and India is best advised to steer clear of the Afghan civil war. Predicating any policy on the US’ consistency is risky too.

Therefore, India should never contemplate a Faustian deal allowing Pentagon’s basing arrangements on its soil for the upcoming Afghan operations as quid pro quo for raw materials for the Covid-19 vaccine. This should be delimited as a purely commercial transaction between the Indian vaccine manufacturing company and the US supplier of raw materials.