General Kenneth F. McKenzie, commander of the United States Central Command (R) called on Kurdish commander General Mazloum Kobani at unspecified location in Northern Syria in July 2019. File photo

No one would have thought that out of the US president Donald Trump’s decision three weeks ago to withdraw all American troops from Syria, a US military re-engagement with renewed vigour in that country would ensue. The US troops were first sent across to Iraq, but only to return to Syria with heavy armour and weaponry. Plans are afoot now to reinforce the deployments.

The remarks by the US Defence Secretary Mark Esper in Brussels on the sidelines of the NATO Defence Ministers meet on October 25 and at a detailed press briefing at the Pentagon on October 28 throw much light on the US intentions (here and here). New templates are appearing. The US’ approach takes three main directions.

First, Washington is exploring a role for western allies. To quote Esper, “I spoke with our (NATO) allies about the situation in Syria. I… called on other nations, who have much at stake, to offer their support to help mitigate the ongoing security crisis… A number of allies have expressed their desire to help with the implementation of a safe zone along the Syria-Turkey border.”

Evidently, these are ideas in nascent form, especially the German plan for Northern Syria, and on November 14, Washington is hosting a meeting of the US-led coalition in Syria.

Moscow has warned against any NATO intervention in Syria and It is unlikely that the EU will act without some form of UN mandate, which will require Russia’s concurrence. But since the safe zone has a huge bearing on the EU’s refugee problem, European capitals may seek some role in its running.

The second aspect of the US’ policy re-orientation relates to military deployments. Although US has withdrawn its “less than 50 troops or so from the immediate zone of (Turkish) attack”, the deployment remains unchanged at the An Tanf base in southern Syria’s tri-border point with Iraq and Jordan (through which the critical M2 Baghdad-Damascus Highway passes.)

The US garrison at Al Tanf at tri-border point in southern Syria strategically overlooks de-confliction zones

Washington has ignored repeated Russian protests about the An Tanf base and estimates it to be a counter to the Russia-Syria-Iran coalition’s residual influence in the area.

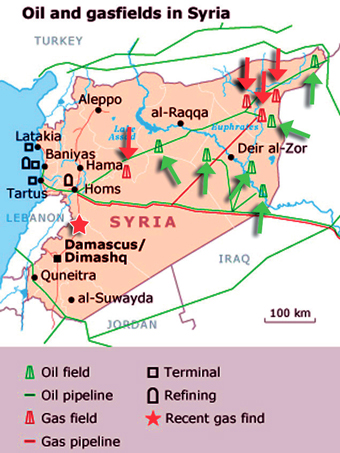

However, it is the third aspect of the US approach that will likely open the Pandora’s box, as it were — Trump’s decision to seize oil fields in the Deir ez-Zor Governorate near Syria’s border with Iraq and along the Euphrates River.

Esper confirmed that an unspecified number of American troops and materiel are being sent to guard the oil fields held presently by Kurdish forces. He flagged the repositioning of “additional assets into the vicinity of Deir ez-Zor”, including mechanised forces and “other types of forces” and added that reinforcements “will continue until we believe we have sufficient capability.”

Esper emphatically warned that the US will “respond with overwhelming military force against any group that threatens the safety of our forces there… These oil fields also provide a critical source of funding for the SDF, which enables their ability.”

The implicit warning to Moscow and the US’ intention to continue with the alliance with Kurds, beef up their financial resources and military capability, and being a provider of security for their homelands in the east of the Euphrates — all this constitutes a controversial escalation. It has already brought Russia, Iran and Turkey on the same page.

The oil fields are vital for Damascus and the majority of the oil comes from the fields in the country’s northeast. The US, on the contrary, is determined to scotch any chance of Kurdish forces in the area and the Assad regime striking a deal (under Russian watch) to return the oil fields to Damascus’ control.

Simply put, the struggle for control of Syria’s eastern oil fields has little to do with fighting terrorism but forms a crucial template of the geopolitical struggle.

Without doubt, the US is reinforcing its dealings with the Kurds and making it a self-financing alliance. But how could Moscow and Damascus reconcile with the fact that US is controlling around 30 percent of Syrian territory?

Similarly, Turkey stares at the spectre that the US-sponsored consolidation of a Kurdish homeland just 30 kilometres away from its border with Syria is set to gather momentum. Both Trump and Esper have found habitation for Kurds as heroes in the American folklore.

The US finds in the Syrian Kurd something rare in the Middle East — an ally, a spirited fighter and also a good friend of Israel. Clearly, the US will not be deflected from its path of creating an autonomous Kurdistan in Syria, which becomes a base for US-Israeli regional strategies.

Turkey will view this as a threat to its sovereignty and territorial security, considering that Syrian Kurdish militia (YPG) is a franchise of the PKK. Ankara has reacted strongly against any move to host the YPG boss General Mazloum Kobane in Washington.

Suffice to say, Trump’s plans for the oil-rich Euphrates Basin will seriously undermine the scope for any serious Turkish-American rapprochement. Turkey can only become more beholden to Russia and Iran in the making of post-war Syria.

The noted scholar and author on Russia and Eurasian studies Michael A. Reynolds at the Princeton University concluded an utterly fascinating essay recently entitled TURKEY AND RUSSIA: A REMARKABLE RAPPROCHEMENT:

“The inability, or unwillingness, of American policymakers to craft policies that take into account the fundamental security concerns and sensitivities of a country that has, for decades, been a key partner of the United States in the Middle East, the Balkans, the Black Sea, the Caucasus, and Eurasia must be central to any explanation of the current turn in Turkish-Russian relations. The mutual willingness of Washington and Ankara to rebuild their ties will be the key determinant of the future of the Turkish-Russian relationship.”