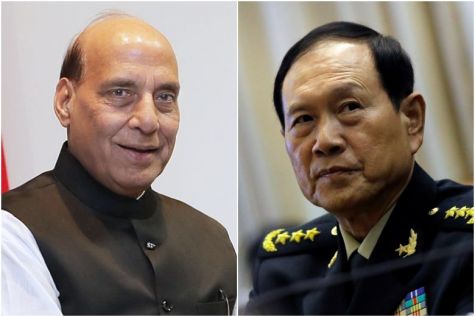

Indian Defence Minister Rajnath Singh (L) and Chinese Defence Minister General Wei Fenghe (R) are due to meet in Moscow on September 4, 2020

Indian Defence Minister Rajnath Singh (L) and Chinese Defence Minister General Wei Fenghe (R) are due to meet in Moscow on September 4, 2020

The legend is that the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, during his pathbreaking visit to India in 1955, was reputed to have told the Indians that all they had to do for Russian help was to give a shout across the Himalayas. I don’t know how far this is true but it has an irrepressibly ‘Khrushchevian’ ring about it alright.

This came to my mind with the news appearing that the Chinese side has proposed a meeting between the defence ministers of India and China who happen to be in Moscow to attend the SCO meeting. It is a reasonable presumption that the meeting will take place today.

One would assume that the Russian hosts have done their part in facilitating this exchange, the first political level meeting since the India-China standoff began in early May. What is absolutely certain is that Moscow is seized of the India-China standoff and its grave implications for regional security and stability.

Having said that, the international environment remains complex and complicated. The tensions in Russia-US relations are at their highest level in the post-cold war era. On the other hand, Russia-China relations are at their highest level in history.

The Modi government has keenly fostered close relations with the US, especially in the most recent past, while India’s relations with China have touched a historically low point since the normalisation began in the 1980s.

The two “triangles” — US-Russia-China and the US-India-China — do not necessarily overlap. But in the prevailing calculus, they create synergy. What goes to India’s advantage is that it has excellent relations with both the US and Russia. Whereas, China’s relations with both the US and India remain tense, but then Beijing also seeks cooperation with both countries.

From the Russian viewpoint, it remains a matter of satisfaction that despite India’s deepening ties with the US, and notwithstanding growing pressures lately from Washington on Delhi to whittle down its relations with Russia, the Russian-Indian relationship continues to be resilient in adapting to newer and newer conditions in a world order in flux.

Neither side is making undue demands on the other. Contradictions could appear if India edges closer to the US’ “Indo-Pacific strategy” (a code word for containment of China.) Russia has deplored the US’ strategy. But that is for the future.

Meanwhile, the rising tensions in India-China relations coincide with a significant deepening in the Russia-China relations in the most recent period, as Moscow and Beijing have drawn closer to push back at US hegemony.

A high level of coordination and cooperation between Moscow and Beijing is apparent. For example, they worked closely to defeat the US move on “snapback sanctions” against Iran. Again, in a recent message to Chinese President Xi Jinping, Russian President Vladimir Putin expressed readiness “to continue active efforts jointly with its ally China in order to prevent wars and conflicts in the world and ensure global stability and security.”

The military standoff in Ladakh has necessitated a big build-up of the Indian armed forces and Delhi is sourcing Russian weaponry. Defence Minister Rajnath Singh is presently on his second visit to Moscow in the past 2-month period.

The Russian connection is crucial for India also for another reason. Russia is the only country that can act as facilitator for any eventual Chinese-Indian rapprochement. The Russian diplomacy has shown to be adept at sequestering the country’s respective relationships with India and China.

All in all, in today’s circumstances, Russia has become a uniquely placed indispensable partner for India. Importantly, this is also the finest foreign policy legacy of Prime Minister Narendra Modi under whose watch the India-Russia relationship steadily regained its verve.

Nonetheless, one should not overestimate Russia’s capacity to moderate the India-China border standoff. There are severe limitations in wading into boundary disputes between any two countries that impinge on their sovereignty and territorial integrity. This is one thing.

More importantly, the crux of the matter today is that a dangerous situation prevails in eastern Ladakh. Realistically speaking, a restoration of “status quo ante” or an unconditional disengagement by the PLA frontline troops is not to be expected. In the Chinese perception, fundamentally, Delhi has been pursuing “Mission Creep”, which is not acceptable.

Our sanctions lack any real bite. And our “Tibet card” and the “Quad” won’t impress the Chinese, either, and if we push the envelope, a severe blowback is almost sure to happen that may belie predictions. On the other hand, a prolonged standoff or race of attrition would put intolerable burden on Indian resources.

The ubiquitous Americans are no longer the top dog in Asia-Pacific. In any case, it is unrealistic to expect them to do heavy lifting — deploy force, risk war, expend serious resources and invest America’s prestige and credibility — on issues that don’t relate directly to their vital interests or problems.

The public opinion in America militates against any entanglement in a military conflict. To be sure, the US faces a conundrum since it is trapped in this region but can neither transform it nor entirely wash its hands off it — be it Afghanistan and Central Asia or Pakistan and Iran.

Above all, the US’ domestic priorities will and should take precedence over any adventures abroad that are likely to absorb large resources or the president’s time. Evidently, squaring the circle in eastern Ladakh is going to be difficult even if we were to give a shout across the Himalayas.